Unpack the Perceptions – Addressing Child Labour by Reversing the Low Perceived Value of Education

Policymakers, education stakeholders and development specialists everywhere should take note: it is estimated that today, according to UNICEF, slightly more than 1 in 5 children (between the ages of 5 and 17) in the world’s poorest countries work to help their family make ends meet. That figure equates to a breath-taking 160 million children worldwide, labouring under perilous conditions and potentially risking their long-term health and development, instead of going to school. Though it may seem like a foregone conclusion that for many parents, access to quality education would be first and foremost in the order of priorities for the children, that proposition is not without its share of caveats. Sensitising communities, especially those who subsist on the margins, to the value of education, working hand-in-hand and building trust with people on the ground may, on its face, seem to be the most basic of solutions that go without saying, but its importance cannot be overstated.

Of course, there are multiple and often overlapping barriers that underlie the incidence of child labour, such as poverty, socio-cultural beliefs, untrained teachers and even lacking infrastructure can play a role in roping off a child’s access to education. Yet what may be less well appreciated is how such factors combine to create negative impressions concerning the value in educating a child. Amid a slow-paced economic recovery from the fallout wrought by COVID-19 in West Africa, where the percentage of people grappling with extreme poverty has been ticking upward since 2020, navigating this dynamic is particularly salient.

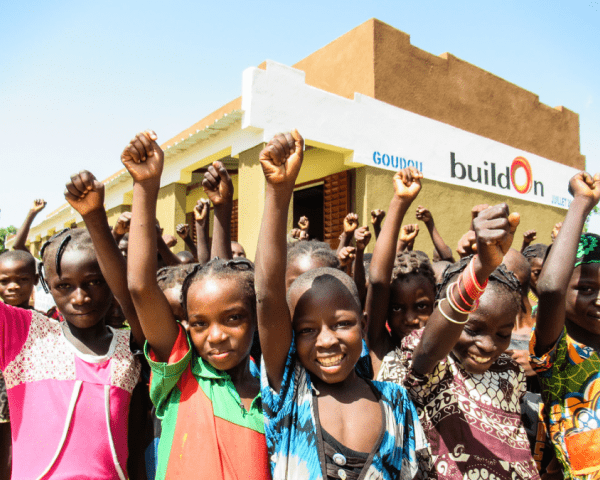

Assane Ngom, country director for buildOn Senegal, posits that the perception of education suffers from a complex mix of reasons, chief among which is poverty, a lack of information on the part of parents, and poor-learning environments at the school level. Senegal, in point of fact, saw a rate of roughly 23 per cent of children (27 per cent of boys and 19 per cent of girls) engaged in some form of labour in 2022. Against such a backdrop, Mr. Ngom concedes that for many impoverished households in rural areas, “the education of the [children] is not a primary priority” and even explains that, in some instances, Qur’anic schools, which, due to prevalence and cultural alignment, are popular alternatives.

Moreover, and without mincing words, the country director states, “Education is a long-term investment.” Revealing how rational the decision-making process can be for a family coping with poverty, Mr. Ngom asserts that “a poor family” may not have the luxury of accepting a bargain that pays off “10 or 20 years” down the line, “without a short-term solution” in the immediate future.

That is, perhaps, one of the main reasons why community sensitisation figures prominently in buildOn’s approach. However, he takes pains to point out that although school construction and changing the physical-learning environment for the better are important, sensitising parents through income-generating activities to support their child’s education and manage the school, as well as well adult-literacy programmes in the local language are equally important, if not more so.

Drilling down on this point, Mr. Ngom maintains that, “With adults who have never been to school, if you start doing adult-literacy programmes in these communities, in three months you will find some adults who can read and write perfectly! It is sensitisation... It’s kind of like magic… Now if they can read and write, they know more what they missed when they were [younger] and will not want their [children] to have the same story.”

Cognizance of what works and the effectiveness of community sensitisation imbues a responsibility to act accordingly. The stakes are too high to do otherwise. Sounding a note of caution, Mr. Ngom affirms, “If you only bring education to a community, without supporting that community to be autonomous economically, it will be very difficult” and the risk to children staying in school is not far off, for parents are not equipped to support education beyond enrolment. From there, it follows that the prospect of child labour rearing its ugly head is not far off either.

Admittedly, there is no single or simple panacea to resolving the development challenges that stifle the progress of vulnerable communities the world over. Yet it is perhaps evermore clear that a “whole-of-community approach” – one that provides a real stake for parents – ought not be considered just standard fare, but rather emphasised in efforts to expand access to quality education, particularly when the perception of its value is in question. As Mr. Ngom makes clear: “If the community is involved with the management of the school, they will consider it like their own home...”